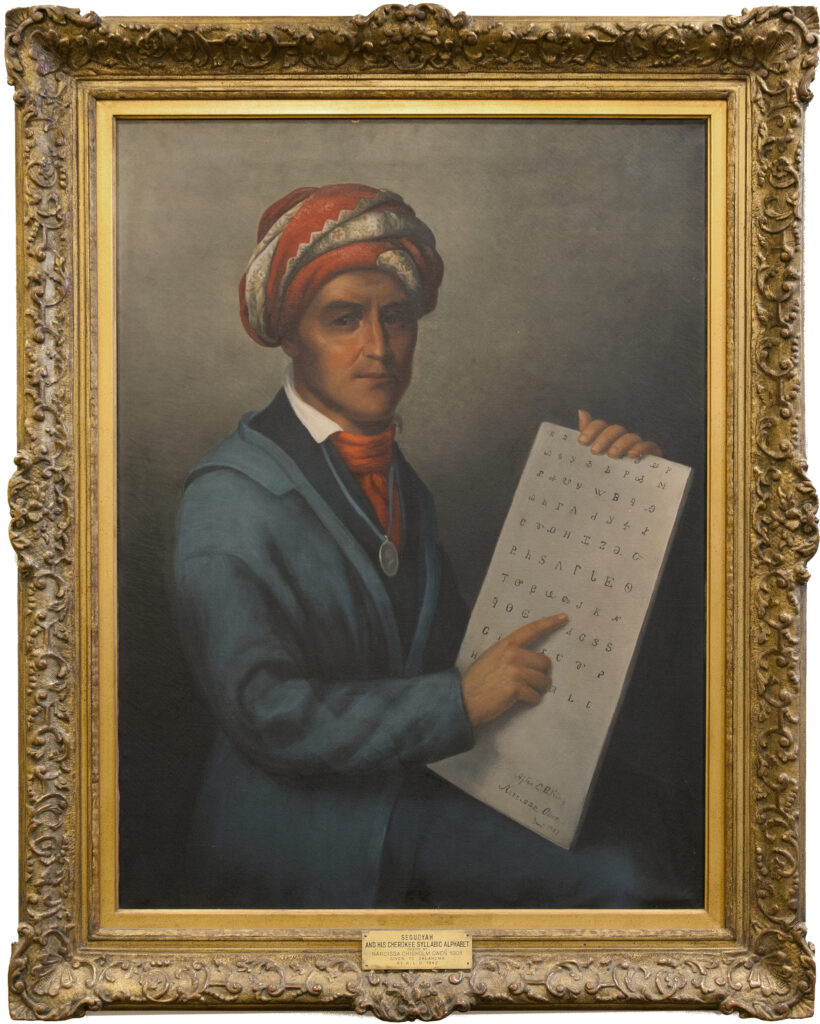

Artist: Narcissa Chisholm

In 1809, an Appalachian silversmith named Sequoyah began working on a method of communication to allow Cherokees to converse with one another in the same way as the European settlers did with their “talking leaves.” He worked on the project for more than ten years and the result was the Cherokee syllabary. In a syllabary, each syllable is represented by a character. Sequoyah’s original syllabary had 86 characters. What is truly remarkable about his invention is that within a decade nearly all of the Cherokee tribe could read and write. Their literacy rate greatly exceeded that of the European settlers in the area.

Sometime around 1822, Sequoyah moved to Arkansas and taught western members of the Cherokee tribe to read and write. Sequoyah was one of the “Old Settlers” – Cherokees who relocated before forced removal of the Trail of Tears. In 1828, he was part of a delegation that traveled to Washington, D.C. to negotiate trade of their lands for land in Indian Territory. It was during this trip that Sequoyah sat for a portrait with Charles B. King. Shortly after returning to Arkansas, he moved to Big Skin Bayou Creek in what is now Sequoyah County. The cabin he built is now a museum operated by the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Narcissa Owen’s father, Thomas Chisholm, was the last hereditary chief of the Old Settlers. She was born in 1831 at Webber Falls in Indian Territory. It is possible that she met Sequoyah at some point before his death in 1843. Narcissa was sent to college in Evansville, Indiana where she studied music and art. After graduation, she taught music in a girls’ school in Greensboro, Tennessee. There she met a young engineer, Robert Owen. The two were married in 1853, in the home of Tennessee’s Chief Justice. When Robert Owen became president of the Norfolk and Western Railroad, they moved to Lynchburg, Virginia. The couple had two sons, William and Robert. William attended medical school at the University of Virginia, while Robert attended Washington and Lee University.

Following the Civil War and the death of her husband, Narcissa and her son Robert returned to Indian Territory and claimed their Cherokee allotment. They built a house she named Monticello in honor of Thomas Jefferson, who had presented her father with a silver Peace and Friendship medal in 1808. Robert studied law and became well known as an attorney in Indian Territory. After Robert married and left home, Narcissa decided to begin painting – at the age of 62.

In 1904, three of her works were included in the St. Louis Exhibition and two won medals of honor. The three paintings were of Thomas Jefferson and his descendants. In her portrait of Sequoyah, Narcissa credits artist Charles B. King for the inspiration for her painting. King’s portrait was published as a lithograph in a collection titled History of the Indian Tribes of North America, with Biographical Sketches and Anecdotes of the Principal Chiefs (Philadelphia, 1838-1844).

Along with painting, Narcissa also became involved in the Women’s Suffrage movement and was a member of the Indian Women’s Woman Suffrage League of Indian Territory. Narcissa’s son, Robert Owen, was elected as one of Oklahoma’s first senators in 1907. He donated the portrait of Sequoyah to the Oklahoma Historical Society in July 1942 and it is on permanent loan from that collection. Appropriately, it hangs in a conference room equipped with long-distance communication technology.